What is an event comic? The most important component of an event comic is magnitude, but one can actually split the understanding of magnitude atwain.

The second meaning of magnitude involves the players: an event comic will step outside of a single book’s story. We are not dealing with the singular but with the collective. The Dark Phoenix Saga (forever butchered on film) in many ways changed comic storytelling, one of the ways involving the sheer magnitude of its story (but it’s importance is because of the small, but that is another conversation) ... but it is an X-Men book, an X-Men story. Crisis on Infinite Earths, the fore-mentioned DC event, involved everyone. As in the book was delayed as its creators researched all the various cracks of DC publishing so as to include it all in the event. The magnitude is not only in the scope of significance, but in the scope of involvement. Event comics bring various characters and teams together.

Now if I were to list every story that involved multiple characters from varying titles coming together and involved considerable stakes and consequences, I would drown in the listing. Arguably the Justice League and subsequently the Avengers were built to tell these stories every issue. Some prospective events fall into subjective limbo. For the purpose of this project, I will include two kinds of events: there is the Limited Series event and the Crossover event.

The Limited Series event is the origin of event comics and still the staple. The publisher puts out a series of issues that tells a story incorporating many of their characters in one grandiose occasion. Using this series as the backbone, the publisher may also let each ongoing series tell their own account or side story of the happenings of the larger event. Por ejemplo, Marvel’s event Civil War was a 7-issue mini-series telling of the fallout of a rift between the ideology of two of its high-profile Avengers characters. However, if you were to boot up the Marvel Unlimited app and click on the reading list for the Civil War: The Complete Event, you would find a list of 97 issues (I know a number of people who have tried to read the event that way, I do not recommend it). You are supposed to get the main story in the limited series and then be able to enjoy your favorite character or team interact with those events in their own particular way and see how it affects their particular world.

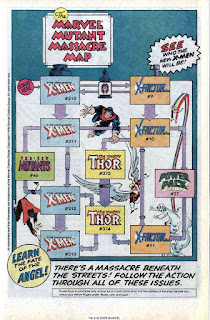

The second form events take is the Crossover. Now crossovers have existed for a long time. Marvel saw the power of them in the 60s as their shared universe brought in readers rather than other publishers fear that it would deter. A crossover involves a story going from the pages of one book, say Batman over to the pages of another, say Ambush Bug. In order to read the story in full, you would need to break out of your rut of buying only the one book and hunt your local spinner rack for Ambush Bug #127 in order to complete your story. And maybe, possibly, cross-their-fingers-and-wishingly you will enjoy the other title enough to begin to purchase that regularly as well (If it wasn’t obvious, comics are business, events are money). But then what makes a crossover an event? That is where you appeal to magnitude and scope, as well as perhaps a third definition of magnitude here, the number of issues.

Why are events important? Event comics are often milestones or markers that newer readers use to situate themselves in the sea of super hero worlds. To return to a former example, I know many people that Civil War has served as either an entry or early gateway into the bigger world of comics. Even for the longtime reader, event comics can introduce the reader to new edges of the fiction. The older events act as time capsules for their eras, a personal love of mine. And they are big. People love big... or they think they do. It is always attractive even if it fails.

Why are events bad? Okay, they aren’t, not objectively. But they can go bad quickly and in many ways. And a lot of that comes back to money. The ideal event grows naturally out of the story. Far more common, they originate as editorial mandates. Or they grow to a scale they should not to increase income. When events are scheduled for the sake of income like a flagpole film franchise, you are promised useless side-series, feckless tie-ins. Events induce gimmicky status quo changes, character death/resurrections design for shock and sales not natural narrative development. And perhaps the most important, already mentioned, is the event comic’s love of the big at the cost of the small. You can tell me a moment matters, you can display character emotions, but that all pales to the reader feeling it in their bones. Readers do not invest in a character and world when it is all threatened. You need them to care first so that the heroic cost has power. Events can lose sight of this or depend to deeply on a reader’s prior immersion into the life of the fiction. Events fall in love with upping the stakes, but can often fail to help the reader care.

Events can go bad quickly... but there is always something exciting and enticing. They are bigger stories than any film can ever hope, with characters that have richer histories than TV shows can manage, with imaginations unhindered by a budget: they hold every kind of narrative promise. And sometimes they even deliver.

First up is the proto-event comic Marvel Super Hero Contest of Champions (Spoiler: it is bad)

No comments:

Post a Comment