When I entered the super hero comic world, Marvel Comics was my chief gate. Most of my DC exposure was a few library comics, some wandering words, and the animated series. Later, I would collect a few of the bigger continuity independent stories of fame but the DC world as a larger whole was empty to me at least in any way that resembled my Marvel knowledge. A roommate who stood on the other side of that epistemic fence would put the limited series Crisis on Infinite Earths (1985) in my hand. Thus would begin my journey into the grander realm of DC continuity.

Writer Marv Wolfman and artist George Pérez began a new phase of DC Comics in 1980 when they would revitalize the previously unremarkable team of sidekicks the Teen Titans in their series... the New Teen Titans. Infusing the book with some of the more dynamic serialism of Marvel, Wolfman and Pérez gave life to a company and an industry that was floundering. Many view this iteration of the Teen Titans as DC’s answer to Claremont’s X-Men, some going so far as to accuse the two of copying Marvel’s Merry Mutants (which is oversimplifying the book at best). Banking on the popularity of this creative team, DC announced their limited series event, Crisis on Infinite Earths... in 1981. It would take until 1985 for them to truly be prepared to rewrite the history of their multiverse.

DC’s continuity was an after-thought throughout the Golden Age of Comics of the 1940s and 50s. Editor Julie Schwartz is generally honored as being the continuity champion when the page turned to the Silver Age of Comics. New characters were reinvented with old names, reigniting imaginations that had long surrendered super heroes to war, horror, western, and monster comics. Maintaining previous truths of their fictional world had always been unimportant in the olden days, but now Schwartz saw a profit in sustaining a consistency between their stories. Even risking recombining their various books into a Justice League in mimicry of their previous Justice Society venture.

Well it all proved a success, but then those who loved the Golden Age characters longed for and began writing them back into comics. And thus the multiverse was born. Earth-1 would house these new heroes and their adventures and Earth-2 would be home to the fore-mentioned Justice Society and its constituents. They would even split tales of their heroes who never saw an end to their publishing history: now there were two Supermen, two Batmen, the Wonder Women were dual. It became a yearly “Crisis” event where Justice League would meet their counterparts and divulge in some interdimensional shenanigans. And the universes exploded from there. DC began to buy out other publishing companies and each adding a new earth to their repertoire. All of this to say, if you were not in the know, good luck finding the road to enlightenment.

Wolfman proposed his event idea as a means to simplify the burgeoning continuity. And so the research began. And years passed. And finally in January of 1985 ,DC’s first event would hit the stands. And the world would never be the same. (That is a very relative term, an ant “changes” the world) They promised that “Worlds will live, worlds will die, and the universe will never be the same.” Perhaps the falsest claim is that worlds plural would live... but we will get to that.

How do you describe Crisis? It is big. This is as epic as super hero epic gets. Wolfman’s research delved into most every realm of the company’s publishing history. Now, we aren’t seeing the romance comics or every one-off story told, but a large landscape of characters and worlds are covered (If anyone sees a Suicide Squad reference, let me know). The book opens with watching universes die. Earths are being consumed by waves of immutable energy. Worlds will die.

The answer to this crisis is The Monitor, a long running tease throughout DC’s comic line. The Monitor’s original plan was as a villain, but Wolfman makes a sudden course correction. Here The Monitor is all that stands against the consuming waves of antimatter. He sends the new character, Harbinger, to assemble an odd assortment of powered beings from diverse time and place. Villains and heroes shoulder to shoulder begin the struggle for reality’s continuing existence.

And the series continues to drift further and further down the DC rabbit hole, as new phases of the struggle include new faces and places. New characters enter the pages, many die. The true villain is revealed and the stakes are put on display. In order to save everything, it must be unified. And here is the genius of Crisis on Infinite Earths as reboot and retcon events go. The reboot is not an accidental and circuitous consequence of the narrative but it is intimately intertwined. The objective of the heroes becomes the editorial decision though they don’t know its full impact on their lives. Often the reboots and retcons can be forced and senseless, leaving the reader painfully cognizant of the editor’s hand.

Ultimately, Crisis on Infinite Earths is a success at the things it sets out to do. Primarily, it successfully entertains. Where Contest of Champions and to a lesser extent Secret Wars is built on the assumption that mashing a smorgasbord of characters together will itself be the selling point, Crisis makes certain the story itself is the reason to read. When you begin with a captivating story, the characters matter exponentially more. I care about their conflicts, confusions, and fears. I turn the page because I am engrossed in the stakes and expansive plotting. When they mourn, you mourn. When they suffer, you suffer. When they endure, you are lifted.

Now, the book is a super hero book. We are not talking about a comic that transcends its genre trappings. Wolfman is not informed by the Moore deconstruction of Swamp Thing or Miracleman. This is Wolfman writing at another level, but one bound up in everything super hero. While he makes his characters more than their powers, they express themselves with the overexpression of a comic. We are not dealing with a work of subtlety. Or perhaps the subtlety is in a different realm than we consider. If anything, the literary quality of Crisis would be in its application of myth. It interplays mythic and religious tropes against the human. We have Pandora’s Box, self-sacrificing godbeings slain by a judas, taoistic duality, sun gods, nether gods: Crisis wears its mythic pedigree upon its crown.

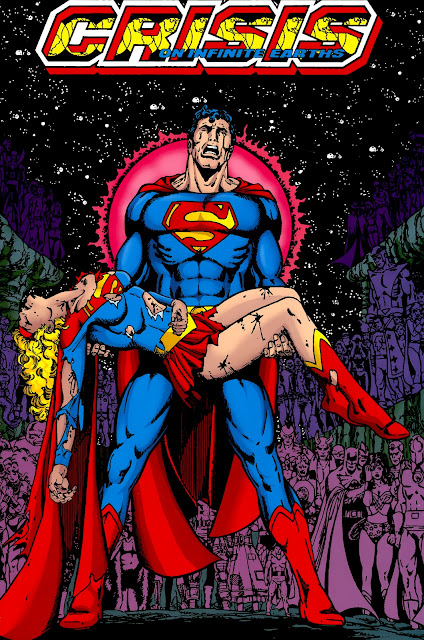

Pérez’s pencils are perfect for Crisis on Infinite Earths. He can pack more on a page than most any artist I know. He is the master of the long panel. He stretches his panels long and slender, allowing him to get far more on a page. But he is the master because they are his best panels, choosing what best conveys the story both through action and atmosphere. He is an artist best experienced in sequence, as a single image is not likely to impress especially to today’s reader. However his characters are emotive actors, portraying their experience before their dialogue. Pérez has a style that honors the Silver Age but is able to take on some of the changes in the medium. He is not as dynamic as the artists to come, but for the purposes of this story, especially as a retrospective, Pérez perfectly answers the call.

Tie-In Comics:

As Crisis on Infinite Earths unfolded over the year of 1985, many of the ongoing comics at the time brought in the effects of Crisis. In a way not seen in Secret Wars, some titles would have their own story that accompanies the events of the event altering their fictional world. These tie-in comics were an experiment in serial storytelling as writers and editors sought how to engage an audience who may or may not be reading the limited series. I would put forward the tie-in endeavor was a success in that the book of Crisis could be read alone and isolated from the rest of the ongoing titles.

The best way to read Crisis, in my opinion, is to read the 12-issue limited series. As for the tie-ins, read them if you are reading the accompanying series as you will then best enjoy how that character experiences the crisis in the midst of their present circumstances. The possible exceptions to this rule are DC Comics Presents #87 which introduces a character that shows up in the pages of Crisis and it feels like there is more. It is not a high quality origin account, but it helps explain a character that I actually think makes little sense in the context of the event. The second exception would be the Green Lantern story in issues #194-198. While Crisis is not a Green Lantern story, a significant portion of its roots in continuity involve Green Lantern mythos. Because of this the story told here, best compliments the event limited series.

Pros:

- This is a wonderful gateway into the greater DC continuity even today. The shear volume of content gives readers the taste of the who and whats of DC. They continue to mine the events of Crisis today.

- Introductions of characters and concepts to the pages of DC.

- It is great. Epic often skews toward spectacle, but Wolfman and Pérez keep the narrative grounded in emotion and consequence. While it is a large tome, it deserves its pages.

- Characters. I understand that I have already listed this twice, but characters are why I open these silly things and I am well rewarded here.

- Unifying a complex multiverse.

Cons:

- The deep dive may be too much pressure for some.

- The writing and art may be dated to some.

- The villain uprising feels like a plot with little payoff.

- Some of the effects of unifying these worlds caused lasting harm. The Justice Society was long troubled to find its new place. The Legion of Super Heroes has never rediscovered its pre-crisis glory.

Final Rating (-5/+5 scale): +3

Should You Read Crisis on Infinite Earths?

Yes.

Okay, maybe the better question is who should read Crisis on Infinite Earths? I do not think I would start anyone’s journey into super hero sillies with Crisis, though for the right person it could be a great hook. If someone told me they wanted to explore DC’s continuity, I would start them here. Honestly, if they wanted to read any DC events, they should begin here. Too many things are spawned here, you will be greatly missing context without understanding Monitors and Multiverses and why the heck is there someone who looks like (oh wait and is also named) Uncle Sam?

Availability:

Hoopla, DC Universe both have it.

What Else Might You Read:

If you want a somewhat more modern take on retrospective of DC’s printing history but with an internal continuity, Darwyn Cooke’s New Frontier is one of my very favorite comics. It is Cooke’s love letter to the DC Silver Age.

If you want a modern take on the Crisis idea that leans more into the inherent metatextual nature of the project, Grant Morrison’s Multiplicity is one of the few good things to come of The New 52.

A unique thing that came from Crisis was the space to tell endings in a genre that is afraid of endings. Alan Moore was given the project to tell a final story for Superman prior to his reboot. Some consider it the best Superman story of all time, Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow. (For my money that award is All Star Superman’s to lose)

There’s also Infinite Crisis and direct rebootive sequels to Crisis, but we will get to those.

The Events Master List:

1) Crisis on Infinite Earths (1985) +3

3) Contest of Champions (1982) -3

Next Event: Secret Wars II (1986)... someone save me.

No comments:

Post a Comment